Server Architecture

As a developer using the Buttplug library for applications, your access to Buttplug Servers is limited to some setup methods. Otherwise, most of your interaction with a server will be via the Client API. It's still good to know a bit about what the inside of the server looks like though, if only so you can understand what's being complained about on social media.

Server and Connections

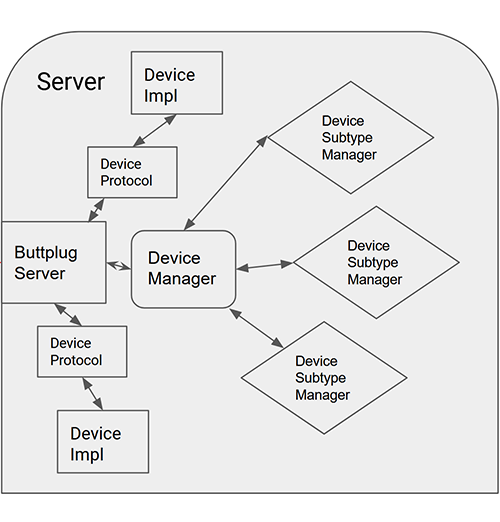

Buttplug Servers themselves don't actually do all that much, as most of the complexity lives in the Device Manager and below. The server portion is mainly concerned with connection management and message routing.

When a client connects to the server, the server handles the handshake. This is where the Client and Server trade identifiers and message spec versions to make sure they'll be able to talk to each other. If any of the information exchanged doesn't match what's expected, the server disconnects.

If the handshake is successful, depending on configuration values the server may then start up a ping manager, which is covered in detail below.

Finally, the server is basically the front door to the rest of the hardware handling system. It receives all messages, and either routes them to its device managers (if they're device related messages) or responds to them itself. The Server rarely has a surface API, and usually just exposes a "ProcessMessage" type method that sends/receives Buttplug Protocol Messages.

Ping Manager

The Ping Manager is an optional mechanism that can help detect unresponsive clients in certain scenarios.

How It Works

- During handshake, the server announces

MaxPingTimein the ServerInfo message (e.g., 20000 for 20 seconds) - If

MaxPingTime> 0, the client must send Ping messages within that interval - The server resets its timer each time it receives a Ping

- If the timer expires without a Ping, the server:

- Disconnects the client

- Stops all devices immediately

- Cleans up all sensor subscriptions

For stateful transports like WebSocket or TCP, the ping system is often redundant. If a client crashes, the transport layer detects the connection drop and notifies the server, which then stops devices automatically. The connection state itself provides crash detection.

For stateless transports (or scenarios where transport-level detection isn't reliable), the ping system provides an application-level heartbeat. If the client stops sending pings, the server knows something is wrong even without a transport disconnect signal.

The ping system may also help in edge cases like:

- Client process frozen but network connection still open

- Mobile apps suspended by the OS without closing connections

- Network issues that don't immediately trigger transport-level disconnects

Ping is disabled by default across Buttplug Core Team maintained server applications like Intiface Central and Intiface Engine. Since we've defaulted to Websocket control for the past 8 years, we had the functionality for basically free. The system continues to exist in the library to leave room for extensibility.

Client Implementation

Reference client libraries handle ping automatically in a background thread or task. You typically don't need to manually send pings - the library does it for you. If you're building your own client implementation, you'll need to implement ping handling when MaxPingTime > 0.

When MaxPingTime is 0 in ServerInfo

If the server sends MaxPingTime: 0, ping monitoring is disabled. The client can still send Ping messages (the server will respond with Ok), but no timeout enforcement occurs. This is common for embedded server configurations or testing scenarios.

The Device Manager

Each server contains a device manager, which does what it says on the tin. It manages devices (and also device communication managers).

The Device Manager holds Device Communication Managers (DCMs), which are responsible for finding and returning devices. It also holds all currently connected devices that have been found and emitted by DCMs. When device messages are forward to the Device Manager from the Server, it parses them to figure out which device should receive the message, and forwards it on.

Device Communication Managers

Device Communication Managers (DCMs) contain the low level implementation of a device enumeration API. These represent different communication busses or management systems, sometimes within an operating system, like Bluetooth, USB HID, Raw USB, Serial, and other messages. They may also implement other communication strategies, network protocols for toys that require network access.

A DCM is responsible for making sure its subsystem is usable (for instance, that Bluetooth is turned on and available within the server host system) starting/stopping device scanning when requested, as well as emitting when new devices are found.

Device Configuration Manager

DCMs need to know what devices to look for. They use the Device Configuration Manager to do this. Device Configuration Managers map device identifiers (Bluetooth names, USB VID/PID pairs, etc) to metadata like device names, proprietary protocols, etc...

If you're interested in what this data looks like, the latest version is kept as JSON at https://intiface-engine-device-config.intiface.com/buttplug-device-config-v4.json.

Whenever a DCM finds a device, it pulls the identifying data and sends it through the Device Configuration Manager to see if there is matching metadata. If matching metadata exists, the information is returned to the DCM, and the DCM continues with making a connection with the device, returning a Buttplug Device, which consists of an Implementation and a Protocol.

Device Implementations and Protocols

After the connection mating dance is finished, the Device Manager will hold a Buttplug Device. This has two parts:

- The Implementation, which is how the library should communicate with the device hardware. This will be things like Bluetooth LE GATT commands, Serial/USB communication commands, etc... These implementations are usually provided as part of a DCM package.

- The Protocol, which is what the library should say to the device to make it do things. Brands usually have their own specific protocols, and some brands may have multiple protocols.

When a server receives a device command, it takes the following path:

- Server receives device command, forward to Device Manager

- Let's say it's a device that vibrates, so the server gets a VibrateCmd command with a device index of 1

- Device Manager takes the device identifier from the command to figure out which device should receive the command, looks up that device, forwards the command to the Buttplug Device

- We find out device index 1 is a Lovense Hush, so it's a vibrating buttplug with one motor.

- The Buttplug Device runs the command through the Protocol it owns, which turns the command from a Buttplug command into a proprietary command.

- When we start here, we have a VibrateCmd, which has a single speed between 0.0 and 1.0, for our example here we'll say it's 0.5. Thanks to the Device Configuration Manager, we know that Lovense toys have 20 steps of power, so we need to get the actual vibration speed, which will be 0.5 * 20 = 10. Lovense's protocol expects vibration messages to look like "Vibrate:X;", where X is the value, so we'll get back "Vibrate:10;"

- Once the device has the proprietary command, it sends that to the Implementation it owns, which actually sends the bytes to the hardware.

- This involves sending the "Vibrate:10;" over the device communication mechanism.

The above list of steps is why you're using Buttplug: We handle all of that for you, across multiple platforms, connection strategies, and toys. :)

Conclusion

Servers are where most of the complexity of Buttplug resides. Getting all of the different communication types and protocols to play nicely with each other is a tall order.

As an application developer, you'll hopefully rarely have to deal with this part of the system.

As a Buttplug Library developer, may god have mercy on your soul.